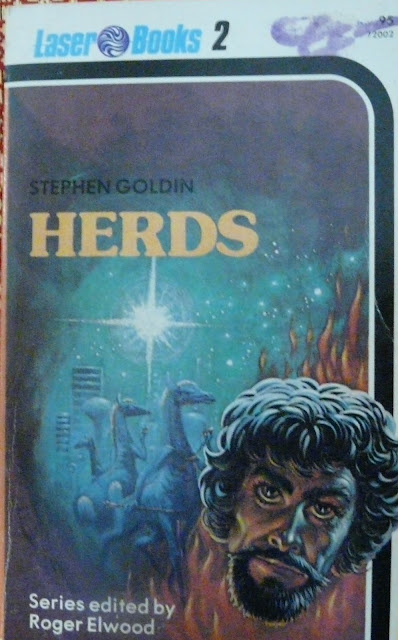

Is it reasonable for one community to concern themselves with the welfare of another community if the two groups share no common interests and the helping community derives no benefit from their service? Stephen Goldin’s obscure science-fiction novel Herds examines this ethical question.

The premise starts with Garnna, a member of the Zarticku who are a race of beings on another planet. Their living conditions might be described as utopian by some ideologues. They are a crime-free society where individuals belong to pod groups referred to as “herds”. The Zarticku are so perfectly honest that simply questioning one about some kind of misdoing will result in a truthful answer which may lead to retraining or re-education in most cases. Rarely, if someone needs to be punished, the ultimate penalty is social isolation, something so horrifying to the Zarticku that few would ever commit such an egregious offense to wind up in that situation.

This is the society in which Garnna lives. His job is to explore other universes, other planets, and the creatures that inhabit them. This is done by separating his mind from his body, making it free to travel vast distances that would be impossible with the limitations of his physical body. So where would an outer space creature from a utopian planet go? You guessed it! Earth! And what country do think he lands in? America! Should this even need to be explained? Originality is not a strong point in this novel.

All the Earthly action happens in the conservative enclave of San Marcos county in California. The locals are red blooded rednecks, a lot like the Texans in Easy Rider who arrest Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper for having long hair and riding motorcycles. In the mountains, on the outskirts of town, a hippy commune has been set up by a social-psychology professor who wants to study why utopian communities typically fail. Garnna sees these two groups as sub-herds within the larger herd of the human race. The professor’s name is Polaski, almost like “Polanski” as in “Roman Polanski”; it’s hard to tell if this similarity is intentional in light of the initial event that sets off the story. Near the commune is a cabin where the wife of a lawyer lives. The lawyer, Stoneham, has political ambitions, so when his wife asks for a divorce, he kills her and tries to make it look like the Manson Family murders by writing “Death to Pigs” on the wall in her blood. His brilliant plan is to frame Polaski for the murder and use this as an excuse to drive the unpopular hippies off their commune. He thinks this will elevate him to the status of hero in the town and make his electoral victory inevitable.

But of course, this is a novel, so something has to go wrong. While Garnna is out of his body and exploring the great and glorious country of America, he witnesses Stoneham’s murder. Since he is invisible, being out of his body and all, Stoneham does not know of his presence so he proceeds with his plans to whip up a lynch mob to run the commune members off their grounds. Garnna, feeling disgusted by the murder and the motive, goes back to the Zarticku and asks for permission to return and fix the situation on Earth. The Zarticku command him not to go, but Garnna disobeys.

Meanwhile, the county sheriff arrests Polaski at Stoneham’s request even though he has doubts about the professor’s guilt. Then Garnna makes mental contact with a hippy named Debby who has psychic powers that become stronger when she smokes marijuana. Debby proceeds to help Maschen solve the case. Having explained that much, I’ll say this novel isn’t really as far out as it might sound.

The strongest point of the narrative structure is the way the three herds play off against each other. The San Marcos rednecks and the counter-culture commune members are an all-too obvious source of conflict. Adding the Zarticku into the mix adds a whole other dimension. They represent a perfect society, or at least on the surface it seems perfect. The hippies are concerned with creating a perfect society in opposition to the ugly towns people who persecute them for being different. The fact that being different is a crime in both the redneck community and the Zarticku community casts a dark shadow over the utopianism of the Zarticku. In the end, Garnna gets punished for obeying his own conscience and going against the commands of the Zarticku authorities. To a lesser extent, Maschen suffers a similar fate since his pursuit of truth in the murder case will end his career as sheriff. Both characters respond to a moral calling that is higher than simply following orders. In fact, the murder case would most likely not have been solved if Maschen didn’t value truth over loyalty. Serving the common good necessitates individuality at times. Garnna also learns that individuality is sometimes necessary for problem solving.

In the middle of all this is the commune where a collective group of individuals attempt to build a utopia for the sake of a researcher who wants to improve the lot of humanity. The commune in this story fails because the lynch mob attacks them and destroys all their property. Based on research I have read on the topic of communal living, relations with the host society is one of the factors that needs to be effectively managed in order to assure the stability of the commune. Other factors that lead to communal failures include uneven or unfair delegation of work, mismanagement of necessary resources such as money and food, ineffective gatekeeping, poor conflict management, and authoritarian leadership styles. Yes, more egalitarian and democratic leadership strategies tend to foster group cohesion more than strict bullying which tends to cause conflict between leaders and followers. Despite my massive sociological digression, I’ll just say that Stephen Goldin is on to something here.

The tightly-wound narrative structure is a little too neat for my tastes, however. The elements of the story are placed together in an almost geometrical configuration. There are no loose threads or dead ends and everything is orderly, shiny, and wrapped up perfectly like a birthday gift with a bow on top, ready to be delivered safely and quickly to the reader with all parts in order. There isn’t any room for noise in this narrative. In fact it’s so finely-tuned that it runs so much like machinery that it lacks enough emotional depth and unpredictability to make the novel a little lifeless. Personally I’d be happier with a little sloppiness in a book as a trade off for my crappy Windows operating system which doesn’t run smoothly at all. Get that digital junk software running with cybernetic precision and I’ll be a much happier person.

One other positive aspect of Herds is the character development. The text is written as third-person omniscient so we have access to the private thoughts of all the main characters. This is effectively done as each one inhabits a singular mind of their own with its distinct personality and preoccupations. This makes the contrast between each individual bold. The downside of this is that each person is specifically crafted to represent a specific idea, each representing a narrative function in the plot development. Thus, the depth of each character only goes so far and it is hard to imagine any of them being anything other than what they are in this particular story. It is like how when I was in high school and we used to joke about how our teachers all lived in shoe boxes because we couldn’t imagine them having any life outside the school. This isn’t a major problem, but it is something that makes the novel fall a little short of its potential. Then again, the aim of the writing is not excessively high to begin with.

Overall, the biggest problem with Herds is its unoriginality and its predictability. Basing the murder on the death of Sharon Tate and trying to blame the crime on a commune leader named Polaski reeks of manipulation and opportunism considering this was written in the early 1970s. The author probably looked at the Manson murders and thought he had a readymade plot device at his fingertips. The character motivations and the solving of the crime are pedestrian and cliché too. In fact, having Debby use her psychic powers to help Maschen solve the crime comes off as a lazy thinking. Rather than going through the trouble of conducting an investigation and holding a trial, it’s just easier to have a psychic do all the work. The literary realization is less than spectacular in the end.

But what about the moral underpinning of the story? I would argue that it is the strongest point of the book. Garnna lives in a society that is peaceful, meaningful, and socially fulfilling but it is also massively conformist and rigidly authoritarian. His desire to help another herd, the human herd of the hippy commune, leads him to a higher moral calling and the realization that all living creatures are equal and should be treated as such. Helping another community in need is part of this vision, even if it does not bring any gain to whoever does the helping. Herds obviously does not sufficiently exhaust any discussion on this ethical issue, one which has been debated by philosophers from day one, but it does an excellent job of introducing the concept and encouraging further examination.

Herds is not a great book, but as a product of its time, being the 1970s, it is a bit of a curiosity. Its strengths and its flaws run along parallel lines, making it readable but not particularly mind-expanding. It probably works best as a book for younger readers while also being too dated for them to see its historical context. I wouldn’t go far out of my way to find a copy of Herds, but if you see it around somewhere at a reasonable price and have a taste for exploring lesser-known works of fiction, it is worth picking up.

No comments:

Post a Comment