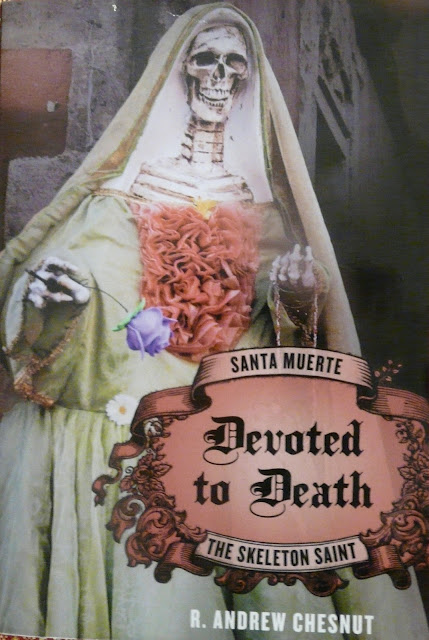

Over the last two decades, interest in a skeleton saint has grown in both Mexico and Latino communities north of the border in the U.S.A. In fact, the popularity has begun to spread outside of Latino communities too as different ethnic groups become familiar with each other. This saint is called Santa Muerte and it has also begun to attract media attention because of its popularity with Mexican drug cartels and other people associated with the underworld. What the media doesn’t tell you is that Santa Muerte’s appeal is wider than realized and in fact most of her devotees are ordinary people without any nefarious intentions. Anthropologist R. Andrew Chesnut sets the record straight in his study of this fledgling religious movement in Devoted to Death: Santa Muerte the Skeleton Saint.

After stating his intention to save the Santa Muerte community from negative publicity, Chesnut examines the history of this saint. He starts by discussing the Uto-Aztecan death goddesses. But he is more convinced that the image of Santa Muerte was not part of pre-Conquest culture and actually arrived with the Spanish invaders and the Catholic church. They brought over images of the Grim Reaper which sprung up during the Black Plague. The intention was to scare the people of Mexica into submission, but secretly some people were secretly putting the Grim Reaper on altars and making sacrifices to him for favors. Similar traditions have proliferated in Central America and Argentina, but these involved a male Grim Reaper and appear to be unrelated to the current phenomenon of Santa Muerte. In recent years, due to syncretism with African diaspora religions like Candomble, Vodou, and Santeria, Santa Muerte has emerged from hiding and taken on a new life.

In Mexico City, a grocery store with a shrine to Santa Muerte started attracting so much attention that the owner began offering monthly prayer and worship services complete with mariachi bands. Another chapel called the Temple of Death opened and the cult has been snowballing in membership ever since. Chesnut uses the word “cult” in the Latin sense of the word “cultus” which means “religious community” and in no way applies to the more current usage indicating authoritarian, high control groups led by charismatic leaders.

Each chapter in this book is about the different ways Santa Muerte is worshiped and petitioned for favors with some commentaries on who her devotees are along the way. Whether people are making offerings for money, work, love, or protection from harm, most ceremonies are relatively benign and innocent. Offerings of candles, incense, food, and drinks are common. The most controversial gifts include alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana. Animal and human sacrifices are mostly the stuff of urban legends and media sensationalism.

While there are Santa Muerte devotees from all walks of life, a quick survey of the book reveals that most of them are working class mestizos like truck drivers, small business owners, police, and prison guards. There are, however, some upper class and educated followers too. Some are lawyers, some are teachers, and some are celebrities or corporate businessmen. A couple people the author interviews are goths with black clothes, nose rings, and tattoos. It should be considered that some people from a counter-culture like that might be pre-disposed to being receptive to a saint whose appearance is that of the Grim Reaper in women’s dress. And while Chesnut does rightfully downplay the media’s negative association of Santa Muerte with criminal activity, he does provide a chapter detailing the appeal of Santa Muerte to drug cartel members and organized crime gangs since altars to the Mother of Death are commonly found on their premises during police raids.

While the author does provide a lot of details regarding the practices and culture of the Santa Muerte cult, he doesn’t do any heavy theorizing and there is only minimal explanation as to why it has grown in popularity. He does identify some causes though. One is that Santa Muerte is available to everybody regardless of class, gender, ethnicity, or position in life. Santa Muerte is also amoral in a way that has caused the Catholic church to condemn her; she is believed to do favors for good or bad purposes without passing judgment on the devotee and that is why doctors as well as drug kingpins can approach her. Santa Muerte has a strong presence in the ambient popular culture too. She appears in novels, TV shows, horror movies, song lyrics, tattoos, and t-shirts. Finally, Santa Muerte is believed to be more powerful than other saints, especially those approved of by the church.

Chesnut doesn’t explain much beyond that. You are left to your own thoughts as to the proliferation of the Skeleton Saint. Personally I feel that the issues of power and condemnation from religious leaders are a part of the appeal. The skeptic in me that doesn’t believe in magic says that there is an equal statistical chance of any saint, spirit, or deity delivering what a devotee asks for in exchange for ritual offerings. There would be a random chance of obtaining the desired outcome no matter who or what is prayed to. But the perception that any one of these supernatural entities is more powerful than the others is what matters to the believer. Therefore as more people align themselves with the cult of Santa Muerte the more stories of successful rituals will circulate socially making it appear that she is the most powerful of them all. Meanwhile, people are more likely to remain silent about the ceremonies that fail creating a socially derived illusion that Santa Muerte ceremonies have a higher rate of success than they really do.

There might also be a subversive element in the worship of Santa Muerte. Since she is not recognized by the church, interacting with her could be a way of rebelling against traditionally accepted authority. This trend might be wider than Santa Muerte since the author points out that Evangelical Christianity is currently catching up in popularity to the Catholic church while African diaspora religions and secular humanism are also making inroads into Mexican society. This would indicate that Mexico is in a time of social transition and attraction to Santa Muerte is one manifestation of that change in answering to people’s needs.

The issue of power might also say something about who follows Sants Muerte. Occupations involving criminal activities on both sides of the law are extremely high risk. Life is just as dangerous for prison guards as it is for prisoners. People who work in construction, poorly regulated factories, the sex industry, or the taxi business are risking their safety every time they go to work. An unemployed man on the verge of going homeless would have extreme levels of anxiety. Santa Muerte, the most powerful saint, often appeals to those whose lives have put them on the front line of danger or despair so it would make sense that they would petition and desire to placate the representative of death to bless them with the gift of life. As for more mundane concerns like winning a poker game, passing an exam, or attracting a lost lover back, those desiring such favors might as well turn to the most powerful saint available. Why turn towards weaker saints? But otherwise the widespread devotion and rapid spread of Santa Muerte’s cult might be an indication of growing social anxiety. If magic is about power and control, than the growing popularity of a religion involving magic might indicate that wide sectors of society feel as though they have little or no control over the circumstances of their lives. While that lack of control could be present at any given time throughout history, the beginning of a new cultural practice addressing that anxiety might be a sign that the old ways are failing and the younger generations are searching for something more effective. Widespread anxiety might be commonplace, but changing cultural practices could indicate that a precarious rupture with the past might be happening.

R. Andrew Chesnut’s intentions here are to clear up misconceptions about Santa Muerte and advocate for the variety of people who are attracted to her rising popularity. It is written for the general reader. This is good because clarifying the beliefs and practices should encourage people to tolerate something about Mexican culture that they don’t understand. It’s too bad Devoted to Death doesn’t go deeper into an analysis and explanation for what is happening on both the south and north sides of the border though. It would be nice to have heard a professional anthropologist’s views on what this says about Mexican society. He just leaves you hanging to draw your own conclusions.

Anyhow, the next time you see a veladora decorated with an image of Santa Muerte, probably beside candles depicting the Virgen de Guadalupe, in a grocery store, a market, or a bodega you can ask the people selling it how to do a ritual. My experience with Mexicans and Chicanos has been that they are usually eager to talk about their culture with non-Latinos like me if you show a sincere interest. You might open some doorways, make some new friends, and maybe, if you’re lucky, you might even be blessed with good fortunes from the Skeleton Saint herself.

No comments:

Post a Comment